When it comes to America's most famous "serial killers", there tends to be substantial intrigue lurking just below the undisputed conventional narrative. In case after case, there's a surprising number of largely-buried facts casting doubt on whether said murderers are truly guilty of all the crimes laid at their feet, or whether they acted alone for the ones they did commit. Many of these anomalous details show up in the authoritative books, TV shows, etc. that chronicle these killers, but are presented as nothing more than interesting factoids with no greater meaning, and gradually disappear from the public consciousness entirely.

Consider the infamous John Wayne Gacy, who was convicted of murdering 33 young men and boys in Chicago during the 70s. There's no doubt Gacy was a monstrous, unrepentant murderer. Yet it's clear, especially in recent years, that Gacy did not work alone. Chicago TV network WGN aired two stories on this in 2012, showing how certain employees/business associates of Gacy evidently helped lure some of the victims while another murder occurred when Gacy was proven to be out of town. A subsequent WGN piece in 2016 made the startling revelation that one Gacy employee was the second-in-command of a Chicago-based nationwide pedophile network; and Gacy was aware of that employee's ties to child sex trafficking. The founder of this ring previously ran a similar operation in Dallas whose clients included "prominent people", making it likely that he maintained a similar client base after moving to Chicago. As it happened, the politically-connected Gacy, who was directly linked to the founder's right-hand man, was keeping a sexual blackmail file on "politician, sports figures, county and city employee[s]".

Besides Gacy, one of the other most prominent US serial killers is Ted Bundy. Officially responsible for murdering dozens of women and girls throughout the United States, he is many people's go-to image of a sociopathic killer, hiding behind the mask of a charming and attractive young man. And for most people, the idea that Bundy wasn't solely responsible for all the murders he's accused of would never even cross their mind. No one could believe something that outlandish, unless maybe they have a demented crush on the man. Right? But the prior example of Gacy is a cautionary tale that sometimes what we all "know" to be true isn't true at all.

When you examine the Bundy case, it becomes clear that there was strikingly little direct evidence tying him to most of the murders attributed to him. Bundy was a suspect in many murders throughout the western US, but the only murders for which he was convicted were the Chi Omega sorority house killings at Florida State University and the murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach. The rest of the official attributions came about from his death-row confessions right before his execution. Some of the reports on his confessions are even contradictory, as we'll see below. Obviously none of this proves Bundy was innocent of these murders, but it does mean that the cases deserve scrutiny as to whether there's actual evidence backing up his involvement (beyond police suspicion and a last-minute confession).

Bundy's alleged crime spree in Florida was preceded by his incarceration in western Colorado. There, he stood trial for the January 12, 1975 murder of Michigan nurse Caryn Campbell. While vacationing at the Wildwood Inn in Aspen CO, Campbell vanished; her bludgeoned body was found one month later in the snow. After some false investigative starts, Pitkin County DA's office investigator Mike Fisher built a case against Bundy, based mainly on credit card receipts placing him near Aspen on January 12 and a purported eyewitness who saw him at the Wildwood Inn that day. Ultimately, Bundy escaped from prison and the trial never completed, nor was it resumed after his Florida sentences were handed down.

But Colorado prosecutors might have secretly been glad that they never had to finish the trial. Something very strange happened at the pretrial hearing, which Bundy chronicler Ann Rule (a former friend of his in Seattle who later authored a book on him) detailed:

This time, the eyewitness was the woman tourist who had seen the stranger in the corridor of the Wildwood Inn on the night of January 12, 1975. Aspen Investigator Mike Fisher had shown her a lay-down of mug shots a year after that night and she'd picked Ted Bundy's. Now, during the preliminary hearing in April of 1977, she was asked to look around the courtroom and point out anyone who resembled the man she'd seen. Ted suppressed a smile as she pointed, not to him, but to Pitkin County Undersheriff Ben Meyers. (Ann Rule, The Stranger Beside Me, p.230)

The witness, Lisbeth Harter, was clearly the lynchpin of the state's case. No other evidence placed Bundy inside the Wildwood Inn, and that evidence evaporated with Harter's identification of somebody other than Bundy. All the prosecutors had left was evidence linking Bundy to the general area on the day in question, an inconclusive and since-discredited FBI analysis placing Campbell's hairs in Bundy's car, and an attempt to introduce murders in other states that Bundy was suspected in but never even stood trial for. It's hard to imagine that a remotely impartial jury would have found Bundy guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Of course, Bundy could still be factually guilty of Caryn Campbell's murder even if the state's case against him was dubious. But on the flipside, how do we know that Bundy really was guilty when the evidence against him amounts to fairly little under scrutiny?

The argument for Bundy's guilt (e.g. by prosecutor Milton Blakey discussing the trial decades later) would posit that Harter just got confused at the trial and made a mistake. After all, didn't she identify Bundy back in 1976 when investigator Mike Fisher talked to her? Once again, that becomes less clear when you look closer at the trial record.

A 1977 motion filed by Bundy's defense shows just how questionable the identification of Bundy really was, in a way that's never detailed in the true crime books and shows:

Virtually everything that Fisher claims about Harter's identification is contradicted by Harter herself. Harter testified that she told Fisher about a "strange man" at the Wildwood Inn back in 1975 when he first investigated Campbell's disappearance. Fisher insisted she never told him about it until they met again a year later and she picked Bundy out of a photo lineup. For her part, Harter also testified that she'd told Fisher about seeing two men, and that her identification of Bundy was not for the man by the elevator but for another standing farther away by a refrigerator. The man by the elevator, on the other hand, was who she identified as Ben Meyers. (And pressed on her identification of the man by the fridge as being Bundy, she expressed doubts about that too.) Fisher's response was basically to say that his own witness was incorrect.

A comically bad start for the prosecution, to be sure, but who should we believe in this situation? In a sworn affidavit, Fisher quoted another witness named Ida Yoder as speaking to Campbell in the elevator before she got off on the 2nd floor; Yoder testified (Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, "Aspen court action for Bundy opens", 1977/04/05) that she never spoke to Campbell. Two different witnesses claiming that Fisher misrepresented their statements suggests the problem isn't with the witnesses. Meanwhile it's not hard to imagine a DA's office investigator "enhancing" witness statements for the prosecution. As we'll see later on, other aspects of Mike Fisher's record are less than stellar as well.

Suffice to say it's not, by any means, clear that Harter saw Ted Bundy at the Wildwood Inn.

Back in 2018, when I first read about Harter identifying undersheriff Ben Meyers instead of Bundy, I found it strange but not inherently damning. Witnesses misidentify suspects all the time.

Still, I was curious about Meyers. The fact remains that he was the one identified as being at the Wildwood Inn that day, exhibiting the same out-of-place appearance that prosecutors wanted to attribute to Bundy. By all appearances, he was a worthy person-of-interest in Campbell's murder. I wondered if there was anything else about Meyers that could rule him in or out as a suspect.

I was not expecting to find, after trawling through search results for "ben meyers" "ted bundy", a detailed webpage linking Meyers to the 1975 murders of multiple young women in western Colorado. To quote the relevant portion:

Grand Junction area citizens were heard to say after Botham's arrest, "it sure had put a stop to the murders". It had not. On December 27, 1975, with Botham jailed, Debra Tomlinson was found dead in her bathtub, just blocks from the Benson home. She had been strangled and raped. All the dead women allegedly used drugs to varying degrees, with the exception of Mrs. Botham.

The public would like to believe lawmen are on their side, but with a turnover rate far in excess of the state average, sexual involvement of nearly a dozen officers (that can be proven) with some of the victims, when the same officers being assigned to investigate their murders when they admittedly alter and destroy evidence, and when the police chief of that time, partied with the victims before their deaths, a feeling of uneasiness tends to develop.

The police chief Ben Meyers was forced to resign shortly after the Tomlinson murder, and was allegedly extensively involved in drug traffic. Botham's investigators found numerous large deposits in account in two banks, but the D.A. objected to a court order for all Meyers bank records and Judge Ela denied it, saying it was irrelevant. Immediately, the chief resigned, clearing all accounts. This man took an undersherrif position in Aspen, Colorado, resigning after Ted Bundy escaped from the Aspen jail. During the Bundy trial, a witness identified Myers as the man she saw leaving the dead nurse's apartment at the time of her murder . . . the nurse Bundy was accused of killing and leaving frozen in the countryside.

Throughout 1975, the city of Grand Junction CO (right near the Colorado/Utah border) was rocked by the murders of numerous young women. All of these women were allegedly tied to local networks of drug trafficking and/or sexual exploitation, which were, chillingly, overseen by local law enforcement. And one of the complicit law enforcement officers was none other than Ben Meyers, who served as Grand Junction's police chief prior to becoming the Pitkin County Undersheriff. The article heavily implied that these crooked members of Grand Junction law enforcement, such as Meyers, were somehow involved in the 1975 murders.

(A side note: the idea of law enforcement facilitating local organized crime, and possibly sanctioning the murders of involved women to keep it covered up, is not as farfetched as it may sound. The Jeff Davis 8 murders, which happened in Louisiana not too long ago, are a well-verified example of exactly what was alleged about Grand Junction in the 70s. All of the victims were women involved in the drug trade and tied to a local strip club owner, the same enterprises as the GJ victims. All of them were drug informants for the police, as was at least one GJ victim. Many of them knew each other, as did multiple GJ victims; in both cases, that makes it far less likely that the killings were random. Witnesses identified members of the Jefferson Davis Parish Sheriff's Office as destroying case evidence or even as suspects in the murders, which, as we will see, is also the case with Grand Junction. And finally, note how the Parish's law enforcement tried to present killings done by an organized network as the work of a "serial killer". Keep that in mind as we explore Grand Junction corruption and how "serial killer" Ted Bundy may tie in.)

Tricky as it would be to confirm allegations about overseeing drug and prostitution rings, I could certainly confirm that Meyers didn't have the best record for a police chief. The middle-aged, married (not for long!) Ben Meyers seemed to have a thing for teenage girls. On New Year's Eve 1975, Meyers was caught having drinks at the bar with a "19-year-old girl friend"; he promised to fire a cop who accused him of buying drinks for this underage girl and threatened the local state liquor inspector as well (Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, "Bar incident revealed after police chief resigns", 1976/01/20). Meyers' resignation as police chief came weeks later, though it allegedly had nothing to do with the bar incident.

Finding where rumor meets truth is never easy. But as I dug into the 1975 Grand Junction murders on-and-off over the next couple years, many of the local rumors detailed in that Web article turned out to be backed by solid facts.

The article was hosted on a website run by the sons of Ken Botham. Ken's wife Pat Botham was one of the Grand Junction victims, murdered on August 22, 1975 along with her across-the-street neighbor Linda Miracle and Linda's sons Troy and Chad. Despite Ken having a solid alibi and having saved Linda Miracle during an earlier attempt on her life back in June (the perpetrator of which Linda never revealed), he would be charged with and convicted of these four murders. Ken is currently serving a life sentence, but his sons both came to believe that he was framed for the murder of their mother and neighbors.

Back in 2015, a man named Blake Higgins met Ken's son Thad Botham and was inspired to start a podcast called Junction exploring the case. The podcast ended with a whimper after just three episodes, but Higgins was able to collect some revealing evidence. Junction's first episode interviewed Butch and Arlene Goad, a married couple in Grand Junction who saw Pat Botham shortly before her murder. According to the Goads, Pat told them that she and Linda Miracle were going to come forward together with news that would shock the whole town. Within a week, both women had been killed.

Pat Botham and Linda Miracle weren't the only victims in an apparent position to know too much. The same was true of Linda Benson, a friend of Miracle's who was herself deeply involved in the drug trade. Colorado journalist Alex French published a book on Benson's murder titled The Killing Season, named after what many Grand Junction residents would refer to 1975 as. At one point, he quoted the police statement of someone who knew Benson through the church:

I'll tell you what, though. Linda was into the drug scene. I believe she had knowledge of the numerous heavy pushers around the Valley and that put her into considerable danger. Once she said to me, "If you only knew who the dealers are . . . big shots." (Alex French, The Killing Season, Kindle location 710)

Marti Talbott, a former Grand Junction resident, published her own book Suspects based on information she observed and heard from others while following Ken Botham's case. One of the men Linda Miracle had been dating at the time of her murder was Mesa County sheriff's deputy Truman Haley. Haley testified at Ken's trial that he took one of Miracle's diaries shortly before her murder, read through to see if it mentioned the June strangulation attempt (the one Ken saved her from), then burned it and threw it in the river.

Curiously, he testified about taking the diary in June despite having told investigators he took it in July. Talbott was told by a female acquaintance of Haley's that he had taken a different diary back in June...one that detailed Miracle's sexual encounters with dozens of Grand Junction cops and possibly other city/county officials. It's not hard to imagine why Haley would cover for this diary by shifting the dates. Nor is it hard to imagine Haley and many others in local government having a motive to want Miracle out of the way. Haley, who was married and having an affair with Miracle, testified that he "only" beat his wife once or twice; he also claimed an alibi of being on dispatch the whole night of the murders, but could produce no records to back himself up.

Talbott received information from yet another source on Linda Benson's murder. This woman had dated a Grand Junction cop, and through him met several others on the force. One day, she noticed a cop she'd met selling drugs to her younger sister at the local middle school; when she confronted him, the cop beat, raped, and threatened her. Her boyfriend, upon learning what happened, got her and her sister out of town and planned to confront the cop who raped her. But that cop caught up to her boyfriend first, and in the ensuing struggle, he was shot with his own gun. Her boyfriend was fired by the police in the wake of his alleged gun mishap, while the cop who sold drugs to children and brutally raped Talbott's source got off scot-free.

This same crooked cop was reportedly seen entering Linda Benson's apartment on the night of her murder (July 25, 1975). A couple months later, 13-year-old Tracy Freitas, who used drugs with her friends and had babysat for both Benson and Miracle, was found drowned in a pond while under the influence. The cop left the police department within days of Freitas' death (officially ruled accidental).

Grand Junction's "killing season" had all appearances of being officially sanctioned by local (Grand Junction and Mesa County) law enforcement. In the end, though, every murder was officially linked to a different lone assailant and said to be unconnected with the others. Ken Botham was convicted of murdering his wife and the Miracles, despite a questionable case and Truman Haley's alarming conduct. Ted Bundy reportedly gave a death-row confession to the April 6, 1975 murder of Denise Oliverson, the first Grand Junction murder victim of that year. In 2009, DNA at Linda Benson's apartment matched serial rapist Jerry Nemnich and he was convicted of her murder the following year. Finally, in 2020, genetic material from the murder of Deborah Tomlinson (on December 27, 1975) was matched to the already-deceased Jimmy Dean Duncan. The last of the "killing season" murders was officially put to rest.

Putting aside Botham's disputed conviction and an unverified Bundy confession, surely we can at least accept the Benson and Tomlinson case closures? They are, after all, backed up by DNA evidence. And in that case, Grand Junction's 1975 murders aren't all connected. Yet even a prosecutor will admit that DNA is merely part of the story. It can place a suspect at the murder scene or with the victim, but other evidence is needed to prove the circumstances of the connection. Think about Julius Caesar, who was assassinated in a conspiracy involving dozens of people. If we could have done DNA on his killing, we'd likely only have physical evidence implicating a subset of the perpetrators; that doesn't make the rest any less guilty.

In Benson's murder (and, as we'll see later, Tomlinson's), the DNA does not intrinsically dismiss evidence pointing to additional perpetrators. The law enforcement M.O. in Grand Junction was reducing organized, institutional murder to the work of lone individuals driven solely by their personal demons. As it was in Grand Junction for its "killing season", Jefferson Davis Parish tried to do for its own murdered women in 2005-2009 by passing it off as the work of a "serial killer". How about the archetypal serial killer Ted Bundy, whose alleged murder spree in Colorado overlapped and even intersected the "killing season"?

When the star witness at Bundy's trial identified former Grand Junction police chief Ben Meyers instead of him, a golden opportunity was handed to Bundy on a silver platter. You might expect Bundy to have begun pushing Meyers as an alternate suspect, especially with the baggage that the Aspen undersheriff had from his former job. Even moreso if, say, Bundy was speaking to chroniclers Hugh Aynesworth and Stephen Michaud for their book project investigating his claims of innocence. Instead, Bundy told them not to bother investigating Meyers.

Starting at 4:36 in a 1980 interview that Bundy gave to Aynesworth and Michaud, he discusses the identification of Meyers:

He acknowledges the "questionable character" of Meyers and mentions numerous rumors "concerning misconduct in the various agencies that had employed him", but brushes them off as "most probably unsubstantiated". Then he goes on to say about Meyers (around 6:00): "I think that while an investigation into his past might turn up a lot of trash and a lot of dirt, I doubt that it would really mean anything for this case."

In other words, Bundy claims that the crooked high-level cop identified by the star witness in the murder he's charged with for is irrelevant to proving his innocence.

Arguably, it comes across like Bundy is trying to protect Meyers' record (and by extension, the entire Grand Junction network) from exposure. So rather than a question of Bundy's guilt vs. Meyers' guilt, is it possible that both men were tied to the same western Colorado murder spree during the 70s? Could Meyers, who transported Bundy from prison in Utah (where he'd been convicted of kidnapping Carol DaRonch) to the Pitkin County jail in advance of the trial, have somehow been previously acquainted with Bundy?

According to police files cited by Alex French, a witness living in the same apartment complex as Linda Benson actually saw Bundy there on the night of her murder:

STEVE GOAD, A race car enthusiast who lived in the Chateau Apartments, saw Ted Bundy on TV and said, Oh my God. That's my boy! He remembered so clearly seeing that face in the parking lot out back on the night Linda and Kelley were murdered. The police brought the hypnotist in to work with Goad. It was around 2 a.m. He looked like he was nursing something that was hurt. Ribs maybe. I looked him dead in the eyes. Cold black eyes that I'll never forget. He was real close. I thought he was going to rumble. (Alex French, The Killing Season, Kindle location 913)

For all the murders that Colorado authorities tried or succeeded at attributing to Bundy, it is curious that Linda Benson's killing received virtually no attention.

So Bundy shows up in a murder (Benson) linked to Meyers, and Meyers shows up in a murder (Campbell) linked to Bundy. It doesn't end there either.

Linda Benson had an older sister named Judy Ketchum Lake, also living in Grand Junction. She was married to reputed drug dealer Phil Lake. On July 8, 1974, Judy was found dead in a Pitkin County campground (Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, "Young Junction woman's death attributed to natural causes", 1974/07/09) and it was quickly ruled to be by natural causes, despite the fact that (Fort Collins Coloradoan, "Body of young woman identified", 1974/07/11) "Her death was first reported as a possible homicide when the body was found".

Judy's family nevertheless believed that she had been murdered. Though the Aspen-based investigator of Judy's death said there'd be an autopsy to verify the cause, the Botham website reports that her body was "suspiciously whisked away and embalmed" before that could happen. That investigator was none other than Mike Fisher, who would later produce the questionable identification of Ted Bundy in the Caryn Campbell case!

The next Colorado murder linked to Bundy after Caryn Campbell's is the March 15, 1975 murder of Julie Cunningham in Vail CO. Was she just a random victim, or was there something more going on? Bundy chronicler Ann Rule revealed that Julie was close friends with the daughter of a prominent Salem OR police officer:

Jim Stovall, Chief of Detectives of the Salem, Oregon, Police Department, takes his winter vacation there [in Vail], working as a ski instructor. His daughter lives there, also a ski instructor.

Stovall drew a deep breath as he recalled to me that twenty-six-year-old Julie Cunningham was a good friend of his daughter, and Stovall, who has solved so many Oregon homicides, was at a loss to know what had happened to Julie on the night of March 15. (Ann Rule, The Stranger Beside Me, p.132)

Jim Stovall had worked for the Salem Police Department for over two decades. His biggest claim to fame was his role in catching local serial killer Jerome Brudos. During that time, the Salem police chief happened to be...Ben Meyers (The Capital Journal (Salem OR), "Salem police chief takes Colorado position", 1973/12/10). Yes, the exact same Ben Meyers who was subsequently the Grand Junction police chief and then the Pitkin County Undersheriff.

Meyers actually nominated Stovall for a national police award in 1970 over the Brudos case (Salem Capital Journal, "Detective Tabbed a Top Man", 1970/07/30). Stovall was one of 11 finalists nationwide, and traveled with Meyers to the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) conference that year (Salem Statesman Journal, "Salem Police Detective Awarded National Honor", 1970/10/04).

It would appear the two were quite close, at least as far as police business was concerned. What are the chances that Meyers gets identified in the trial of Bundy's first Colorado victim, and then Bundy's second Colorado victim is close friends with the daughter of Meyers' trusted former subordinate?

Highly-regarded as he was, Stovall wasn't quite squeaky clean. He attracted some controversy in 1973 when he evaluated a Salem city councilman who'd clearly been driving drunk and let him off without even a citation (Salem Capital Journal, "Stewart gets ride in taxicab", 1973/03/07). The sheriff's deputy who contacted the Salem police had told them over radio dispatch that the councilman asked for special consideration due to his position. But police chief Meyers, who signed off on Stovall's decision to let the councilman go, predictably claimed that this was a normal decision with no special influence.

Meyers didn't exactly leave behind his Salem past either. Stovall's partner on the Brudos case was (as Ann Rule mentions in her later book Lust Killer) another longtime Salem cop named Jerry Frazier. A little over a year after Meyers left Salem to become Grand Junction's police chief, Frazier himself left to join his old boss at the Grand Junction Police Department (Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, "Local policeman completes course", 1975/11/27). He arrived just in time for the "killing season".

Within only a month or two of his arrival, Frazier was already a sergeant and was one of the few GJPD officers given access to highly-privileged statewide intelligence on organized crime (Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, "Local lawman tracking mobsters", 1975/04/29). Meyers, of course, was one of the others.

Frazier is known to have supervised at least one of the 1975 murder investigations: that of Deborah Tomlinson (Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, "Scholarship is memorial", 1975/12/31). Like Meyers, he had somewhat of a mean streak that can be documented, particularly in an incident at the very same bar where Meyers had drinks with a teenage girl. Shortly before Thanksgiving 1975, Frazier and Lt. Ron Smith — "the third ranking officer in the department" before being disciplined over this (Fort Collins Coloradoan, "Policeman demoted", 1976/02/22) — got in a fight with two men at the Timbers bar (Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, "Probe brings demotions, suspensions", 1976/02/20).

If Frazier joined the GJPD just in time for the city's murder epidemic, he also left very shortly after it ended. He returned to Salem sometime in 1976, not long after Meyers resigned as chief. I was later told by an informed source that Frazier spent much of his time in Grand Junction attending parties; this, of course, matches the allegations on the Botham webpage about local cops. This source also told me that Frazier had to leave in a hurry because he was caught sexually abusing underage girls in motel rooms.

Back in Salem working as an investigator for the Marion County District Attorney, Frazier grabbed headlines once again in 1983. His son Jerry Brent Frazier was suspected of burglarizing jewelry from a woman's home, and the elder Frazier (full name Jerry Dean Frazier) told his son to dispose of any property he had stolen. Prominent local cop Frazier was actually charged with obstruction of justice over this (Salem Statesman Journal, "D.A. investigator charged with hindering prosecution", 1983/09/14). Unsurprisingly, the charges were dropped within a month; the special prosecutor incoherently claimed that Frazier telling his son to dispose of evidence was actually "an act of cooperation with the police" (Salem Statesman Journal, "Marion investigator cleared of charges", 1983/10/20).

To make a long story short, Meyers' clique from Salem would not seem to be the most virtuous bunch. So it's curious to see them appear not just in Meyers' story but in Ted Bundy's as well. Unless, of course, the two are the same story.

Bundy's next attributed Colorado victim after Julie Cunningham, and the first of Grand Junction's "killing season", was Denise Oliverson. The Botham webpage alleged that all of the Grand Junction victims other than Pat were involved with drugs; the GJPD case file confirms that Oliverson indeed used drugs, though her precise connection to the narcotics scene is unknown. Very little is known about her in general, and her body has still never been found nearly 50 years later. Only her sandals and bike were found underneath a bridge.

A credit card transaction did place Bundy in Grand Junction on the day of Denise's disappearance; it was actually Meyers who announced this in November 1975 (Greeley Daily Tribune, "Colorado officers want to question man held in Utah jail", 1975/11/01). And immediately before his 1989 execution, Bundy is said to have confessed to her murder; even so, it remains unverified and the GJPD didn't officially accept it as a case resolution until 2019.

Weirder still, there are contradictory reports on whether Bundy actually did confess to the murder. Most sources indicate that he did confess, on tape (Associated Press, "URGENT Governor’s Office Releases Tape Bundy Made Before Execution", 1989/01/26). Yet at least one contemporaneous news article (Daily Kent Stater, "Bundy's death ends ordeal for families", 1989/01/26) reported exactly the opposite:

In Grand Junction, Colo., the father of a woman believed to have been murdered by Bundy said he was relieved, although investigators said Bundy did not confess to the slaying.

“We’re just happy he’s been executed because it should have happened a long time ago,” said Robert Nicholson, father of Denise Oliverson.

Just another example of how the unquestioned details propping up Bundy's murder attributions frequently become clear as mud when they're placed under scrutiny. Not that I think Bundy is innocent; the Grand Junction circles he continually intersects with are arguably more incriminating. But with Oliverson's murder preceding multiple Grand Junction killings that certainly do appear connected to local organized crime, it's fair to ask whether the full Oliverson story involves more than Bundy-the-lone-sociopath.

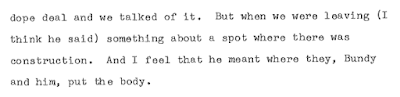

Bundy's parallels with Meyers surfaced well before his alleged murder spree in Colorado. Like Meyers, Bundy originated from a major Pacific Northwest city before relocating closer to the Rocky Mountains. And an obscure statement on pages 603-605 of the police file on Donna Gail Manson (one of Bundy's earliest attributed victims) actually implicates Bundy in the drug trade with a friend named Steve Brown.

This drug trafficking accomplice Steve Brown is also described as a possible murder accomplice to Bundy over a "bad dope deal". In other words, law enforcement was told from the very beginning that Bundy was more than just a lone nut; he was engaged in organized crime and possibly linked to murders for that enterprise.

If true, did that carry over to Utah, where Bundy relocated in the summer of 1974 and lived during the Colorado murders? The circumstances behind the November 8, 1974 murder of Debra Kent suggest the answer is yes.

The best lead investigators had was a strange man hanging around at Viewmont High School that night, where Kent was last seen alive. Before Bundy was a suspect in the murder, the Bountiful UT police investigating Debra's disappearance came up with somebody different: local drug dealer Ronald Dennis Auth. The case file mentions how Auth, a known criminal from nearby Park City UT, surfaced due to his similarity to the composite sketch of that strange man at Viewmont. It goes on to detail how drama teacher Raelynn Shepherd, the main witness to that man, positively identified Auth:

Supplementary Report by Detective Beal

Monday, 11/18/1974Reporting officer and Sgt. Ballantyne pickup up Mr. and Mrs. John Shephard at approximately 1710 hours and accompanied them to Park City, arriving at approximately 1835 hours. At this time we parked our vehicle behind the Club Car 19. While sitting there talking we observed approximately 8 or 9 people walking in the area. Mrs. Shephard pointed out one of the individuals, stating, “That is very close. Is that him?” We replied, “You tell us.”

A few minutes later, approximately 1900 hours we entered the Club Car 19. Mr. and Mrs. Shephard were seated at one table and reporting officer and Sgt. Ballantyne were seated at another table. The suspect in this case was waiting tables this date. Mrs. Shephard observed the suspect when he approached the table that reporting officer and Sgt. Ballantyne were sitting at. She again observed him as he was waiting on another table and again as we were preparing to leave. At that time she was standing facing him.

We left the Club Car 19 at approximately 2030 hours. When we returned to the car Mrs. Shephard stated, “That is the man I talked to in Viewmont,” indicating the waiter, this being Ronald Dennis Auth. Reporting officer inquired as to how she could identify him. Mrs. Shephard stated that there was no question in her mind that he was the man. He looks identical to him, his walk and mannerisms were same, his voice was the same. She pointed out that his voice was slightly higher when he spoke at reporting officer’s table, however when he waited on another table a few minutes later, he was talking in a lower normal voice. This was the voice she had heard at Viewmont. She also pointed out that he was an inch or two taller at this time, however he was wearing shoes tonight with higher heels. She also pointed out that on his left hand he had the imprint of a large ring, which he was not wearing tonight. Reporting officer asked if there was any question in her mind as to whether or not this was the man. Mrs. Shephard replied, “Absolutely none.”

More than just a tentative identification, she was adamant that Auth was the man she'd seen. Shepherd cited numerous specific commonalities, based on physical appearance, gait, mannerisms, voice, and even the imprint of a ring like what the man at Viewmont wore.

Auth was given a polygraph exam and passed, after which he seems to have been discarded as a suspect. Bundy would later be identified by the Viewmont witnesses, but there's a problem. He was also implicated in the abduction of Carol DaRonch earlier that evening, and the timing makes it virtually impossible for any one person to have committed both.

The Murray City Police Department report (pages 73-81 of installment 6 of Seattle PD records on Bundy) detail the approximate timeline that Carol gave to police. Following her arrival at the mall around 7:00 PM, she spent about 10 to 15 minutes inside before meeting her abductor. She then spent (including the abduction itself) 20 to 30 minutes with him in total before escaping. Thus, she would have escaped her captor sometime between 7:30 PM and 7:45 PM, and since she was taken to the police station by bystanders just after her escape yet her report was only taken at 8:30 PM, her escape is likely to have occurred closer to 7:45 PM.

Meanwhile, Shepherd indicated (per the Kent case file) that she first saw the strange man at Viewmont around 7:45 PM:

Written Statement of Raelynne Shepherd

11/10/1974I got to school for the musical at 7:30 p.m., seated my husband in the auditorium, and started around the corner to the dressing rooms. I think it was about 7:45 at the time. The hall was dark, but I could see fairly well. A man who was standing alone halfway down the hall approached me as I walked toward the dressing rooms. He said, “Excuse me, but could you come out to the parking lot and try and identify a car for me?” I said I was busy and asked if he needed any help; if so, I would try and find somebody for him. He said “It’ll only take a few seconds, I just need to find out whose car this is.” I said “I’m sorry” and went to the dressing rooms. His attitude really bugged me as I told my husband that night.

It ranges from extremely implausible (immediately coming up with a new plan and getting from Murray to Bountiful on a rainy evening, all in 15 minutes) to outright impossible (being in two places at once) for any person, Bundy or otherwise, to be responsible for both attacks that night. But that didn't stop Utah law enforcement from implicating him in both anyway.

So how about Ron Auth, whose seemingly-definitive identification was buried by a pseudoscientific polygraph and the questionable link to Bundy? Auth wasn't merely a local drug dealer. He turned out to be a very high-volume drug distributor who received some unusual protection by the justice system.

In 1979, Auth and three others were arrested by the Coast Guard on drug trafficking charges (Morning News (Paterson NJ), "6th 'pot boat' bust nets $34M haul", 1979/06/07). Their shrimp boat, known for humanitarian work in the Caribbean, was hauling 17 tons of marijuana, estimated at $34 million in street value.

Unexpectedly, the federal judge on the case overruled the jury's sentence for Auth and re-sentenced him to just probation (Salt Lake Tribune, "Marijuana Charges Net Probationary Terms", 1979/10/21). Now I'm not "tough-on-crime" by any means, but the system usually is, and often for much lesser offenses than this. Auth had even been quoted estimating the value of his marijuana, which had been imported from Colombia, far higher than the government did: $360 million total. So what happened here? Did Auth just get lucky?

If you think Auth's operation sounds like one of the many organized drug networks operating in Latin America during this time, you'd be right. A particularly notable case, spanning from the mid 70s all the way until its bust in 1981, was Operation Sunburn. Based in the Miami area, the network imported countless millions of dollars in Colombian marijuana and used shrimp boats for transportation, just like Auth. The drug traffickers included local businessmen, lawyers, and a number of Cuban exiles who had worked for the CIA.

Ringleaders Clyde Cobb and Cliff Wentworth (Cobb's attorney) were both based in Fort Lauderdale FL. So were the racecar-driving brothers Bill and Don Whittington, who Cobb financially sponsored; the Whittington brothers would later be convicted for marijuana trafficking during almost exactly the same period that Sunburn operated (Sun Sentinel, "RACE DRIVERS CHARGED IN DRUG CASE", 1986/03/11). At the time of their arrest, the Whittingtons were said to run "a $16 million empire" that included "a Vail, Colo., penthouse".

One day after the Sunburn indictments were handed down in Florida, another operation transporting Colombian marijuana on shrimp boats was busted (New York Times, "20 TONS OF MARIJUANA AND 33 SEIZED IN L.I. RAIDS", 1981/09/04). The timing and the Miami-area involvement in both operations makes it quite likely the two were linked. Importing marijuana into New York and New Jersey, the ringleader was DeCavalcante mob family member Joey Ippolito. Ippolito had contracted the trafficking out of South America to a Fort Lauderdale businessman (of sorts) named Allen Rivenbark.

Also active throughout the same time as Operation Sunburn, Rivenbark was connected to many organized crime partners over the years. His underworld associates included Nixon financier Robert Vesco, Jewish mob kingpin Meyer Lansky, and key members of the Colombo and DeCavalcante mafia families. Drug investigators had been aware of Rivenbark's activities since the mid 70s, but somehow he never seemed to face charges even when his co-conspirators did.

Like the Whittingtons, Rivenbark owned property near Vail CO. His venture, the Black Mountain Guest Ranch, was identified by the feds as a "hideout for East Coast Mafia figures" as well as a distribution spot for drug trafficking throughout Colorado ski resorts (which likely means around Vail and Aspen). Rivenbark and six associates were on their way from Fort Lauderdale to the ranch when their plane crashed on November 18, 1981, killing everyone aboard.

So to summarize:

- Ron Auth, an international drug trafficker living in the area, is pretty solidly implicated in Debra Kent's murder. He gets dismissed and Ted Bundy conveniently fills that spot, despite it being logistically impossible to commit that murder if he was guilty of kidnapping Carol DaRonch. Later, a federal judge largely protects Auth from consequences for trafficking (by Auth's own account) hundreds of millions of dollars worth of Colombian marijuana.

- In Fort Lauderdale, multiple interrelated drug rings with CIA and mafia connections are trafficking Colombian marijuana in the same manner as Auth. The operations run from at least the mid 1970s until 1981. Caryn Campbell — whose murder is attributed to Bundy despite the star witness identifying alleged drug-runner Ben Meyers — happens to be the sister of Fort Lauderdale police officer Bob Campbell (Detroit Free Press, "Nurse's Death a Homicide, Colo. Investigators Believe", 1975/02/20). The mafia is certainly known to go after family members as retaliation.

- These same Fort Lauderdale traffickers are connected to Vail or nearby cities, and some even run trafficking operations there, including at ski resorts. Bundy's next Colorado victim Julie Cunningham, murdered in Vail, is good friends with a Vail ski instructor. This friend happens to be the daughter of Meyers' former close colleague Jim Stovall, himself a part-time ski instructor in Vail as well.

By the summer of 2020, I had a working theory that Bundy operated similarly to how I described John Wayne Gacy above. He undoubtedly was a sociopathic murderer, but he operated as part of a larger nationwide group linked to organized crime and local political corruption. Far from how a "serial killer" chooses arbitrary victims within a target group, this group often selected victims for specific reasons in furtherance of their criminal enterprise. Between all the murders in which he was implicated, Bundy was some mixture of killer, co-conspirator (at the scene or involved in the planning), and patsy (implicated to protect more important members of the group).

But this theory was high on tantalizing connections and low on definite evidence establishing these links as meaningful. The most viable avenue to explore further seemed to be the well-established corruption in Grand Junction CO, revolving around crooked cops like Ben Meyers, Jerry Frazier, and Truman Haley.

So in hopes of finding more solid facts to work with, I sought out the Grand Junction Police Department report on Linda Benson's murder. Her case had been closed in 2010 following the conviction of Jerry Nemnich. Whether or not I believed that was the whole story (I didn't), the GJPD's decision to close the case meant they were obligated to release the case file to the public, so I got a copy.

Early on in the report (page 85), there was an interesting mention of a "John Antanopolis" who had apparently been investigating the Linda Benson and Botham/Miracle murders:

With the benefit of hindsight, it's worth asking why this name was left unredacted among multiple other witnesses whose names were blanked out. Did police want researchers finding this guy? Back then, however, I was just elated to find a lead I could pursue.

I tracked down this individual, John Antonopoulos, thinking they might be another researcher who I could share notes with. And after getting past the initial "how did you find me"-type awkwardness, it actually seemed to be even more promising than that, beyond my wildest dreams. He immediately outlined a series of allegations against Ben Meyers as a murderous local kingpin. As we talked, he became impressed at how I was on the same page as him, had been investigating this for a while, and took the initiative to track him down.

JA presented himself as a citizen investigator who'd been fighting to expose the Grand Junction situation for a long time, tape-recording the involved parties in preparation of a big expose. (For instance, he said he possessed a recorded conversation with law enforcement where they admitted that Bundy's death-row confessions to the Campbell and Oliverson murders didn't exist.) He claimed to have a mountain of evidence that would definitively prove Meyers was behind Caryn Campbell's murder, the 1975 Grand Junction murders, and Ted Bundy's two escapes from prison in Colorado. Best of all, JA acted impressed enough with my comprehension of the case that he believed I could be the writer who assembled his evidence into cohesive form and exposed it to the world.

You can imagine how excited I was: having studied a case for years without much progress, and then suddenly being handed its solution. I knew there was a reasonable chance this could be nothing but talk, and wasn't getting my hopes too far up until I saw the evidence for myself, but at the same time it felt promising. What were the odds that this other person had connected the relatively-obscure Bundy/Meyers dots in what appeared to be the exact same way I had?

Very high, as it turns out, but I wouldn't know that until I realized who I was dealing with.

(Continued in the upcoming Grand Junction's Grand Conman: John Antonopoulos)